On a chilly evening in January 2006, enroute from Islamabad to Muzaffarabad in my host’s hatchback car, we passed through a small town called Abbottabad which is part of Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Abbottabad for all practical reasons is an extension of Pothwari-speaking area of Pakistan, which includes Islamabad-Rawalpindi area and northern Pakistan-occupied Jammu and Kashmir. He stopped the car briefly to buy its famously sweet oranges, and I thought nothing of it.

That fleeting roadside moment was my first and last encounter with a place that five-years-later, would dominate global headlines. On May 2, 2011, while travelling from the United States to India, I switched on my seat-back television mid-flight and heard President Obama announce that the world’s most wanted man, Osama bin Laden, had been killed there bringing to an end a decade-long, meticulously executed search. Instantly, I was reminded of that journey.

Also read | U.S. CENTCOM chief Gen. Michael Kurilla terms Pakistan a ‘phenomenal partner’ in counter-terrorism

That the U.S. Operation Neptune Spear to hunt down Osama took place deep inside Pakistan, far from the Afghan border, was a telling reminder that in future relations between Washington and Islamabad would always be shadowed by a measure of mistrust. The facts of the preceding and following decade also hinted that. As the United States waged its war in Afghanistan and pursued Osama Bin Laden (OBL), a complex partnership emerged between the two countries. Karachi, Pakistan’s key port city, became the hub through which American logistics were landed before making their way to Afghanistan.

Surrounded in red fabric, a compound is seen where locals reported a firefight took place overnight in Abbotabad, located in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province on May 2, 2011. Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden was killed in a firefight with U.S. forces in Pakistan ending a nearly 10-year worldwide hunt for the mastermind of the Sept. 11 attacks.

| Photo Credit:

Reuters

Misunderstandings frequently arose, with the U.S. questioning Pakistan’s sincerity and, on several occasions, American personnel and supplies were looted or ambushed, highlighting the fragile and often tense nature of the alliance.

Pentagon and the Pakistani military’s enduring relationship

After the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan under the Biden administration, it was widely assumed that Pakistan’s strategic as well as tactical importance to the U.S. had ended for long apart from the mistrust owing to OBL killing. Economically, it offered little leverage, and with Afghanistan no longer a priority for counterterrorism, Washington’s focus appeared to shift elsewhere. In this context, the renewed U.S.–Pakistan engagement, epitomized by visits of General Asim Munir to the U.S., including a luncheon meeting with President Trump has surprised many and become a subject of global discussion, including here and elsewhere with numerous popular Western publications also covering the development.

Several factors have been cited for the recent turnaround in U.S.–Pakistan relations: the discovery of rare earth minerals, the potential deployment of Pakistani troops in Middle East to serve the U.S. interests, Pakistan-centric developments in cryptocurrency, which reportedly may involve one of the U.S. President’s sons or Pakistani diplomatic corps ability to charm President Trump. While all of these factors may or may not have some relevance, a less discussed but enduring element is the relationship between the Pentagon and the Pakistani military, which never fully disappeared and often comes to the surface during Republican-led administrations in the U.S. This dynamic requires a detailed unpacking as this is critical to the understanding of some of the present developments.

Also read | India, Pakistan both partners of U.S. with different points of emphasis: Biden administration

In international affairs, our analyses are often shaped by our own conditioning — the lens formed by the place and perspective from which a piece is written. When one tries to step into the shoes of the U.S. establishment and its own canvas, the picture gains clarity. Pakistan is not merely viewed as a South Asian country by the U.S. establishment, even if culturally it is. Geographically, it occupies a critical position, sharing borders with Iran and Afghanistan, and its religious dimension adds strategic significance.

In the U.S. government’s institutional architecture, Pakistan is frequently grouped with the Middle East and North Africa across several major bureaucratic structures, particularly within the State Department and the Department of Defense. The Pentagon’s U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) includes Pakistan in its area of responsibility (AOR) alongside the Middle East and most of Central and South Asia, excluding India. This deliberate arrangement places Pakistan in the same strategic “theater” as Middle Eastern states, reflecting shared military logistics routes, forward basing considerations, and overlapping security challenges.

At the U.S. State Department, Pakistan falls under the Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs (SCA). However, at higher strategic levels, especially within National Security Council (NSC) planning and in earlier regional constructs, Pakistan has often been treated as part of the “Near East” (the State Department’s term for the Middle East). Functional groupings in areas such as counterterrorism and energy security have reinforced this alignment, linking Pakistan with Near Eastern Affairs (NEA) countries due to its Islamic world connections and strong Gulf ties.

Historically, during the Cold War and into the early 2000s, Pakistan appeared on “Afghanistan–Pakistan” desks that overlapped with Middle East policy portfolios, reflecting its pivotal role in the U.S. engagements involving Saudi Arabia, the Gulf states, and Afghanistan. Mirroring the U.S. institutional structures, many multilateral organizations, particularly in the realms of peace and security, mirror similar framework in their daily work.

Now coming to broader political domain, one has to go with the empirical evidence. The Republican Party-led U.S. administrations have traditionally had a soft corner for the Pakistani military. The Central Treaty Organization (CENTO) was established in 1955 during the presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower, a Republican and a celebrated former World War II general. In Pakistan, the agreement came into effect shortly after the military took power in 1958 under General Muhammad Ayub Khan, who replaced President Iskander Mirza in a coup. Unpacking the tenures of President Richard Nixon and President Ronald Reagan, both Republicans, one will find that under both administrations Pakistan’s accessibility to the U.S. aid, both financial as well as military, expanded exponentially. For instance, during President Nixon’s tenure, the Secretary of State Henry Kissinger famously made a secret trip to Beijing via Pakistan in July 1971, even faking a bout of diarrhea to explain his temporary disappearance from the public eye.

President Nixon (right) talks in his White House office on September 18, 1973 with Pakistan’s Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto

| Photo Credit:

THE HINDU ARCHIVES

Pakistan played a role in this process, alongside other channels, including the U.S. State Department officials in Vietnam and France who were actively working toward the same objective. There were also indications from the Peoples Republic of China (PRC) that it sought the UNSC membership, and the U.S., as a permanent member of the Security Council with veto power, wielded significant leverage in this matter. The PRC did become a UNSC permanent member on October 25, 1971 as a result of the U.S.-PRC détente. In any case, Pakistan’s geographic position appears to have been a decisive factor, as evidenced by Kissinger’s visit.

Pakistan’s role in pushing back Soviet invasion of Afghanistan

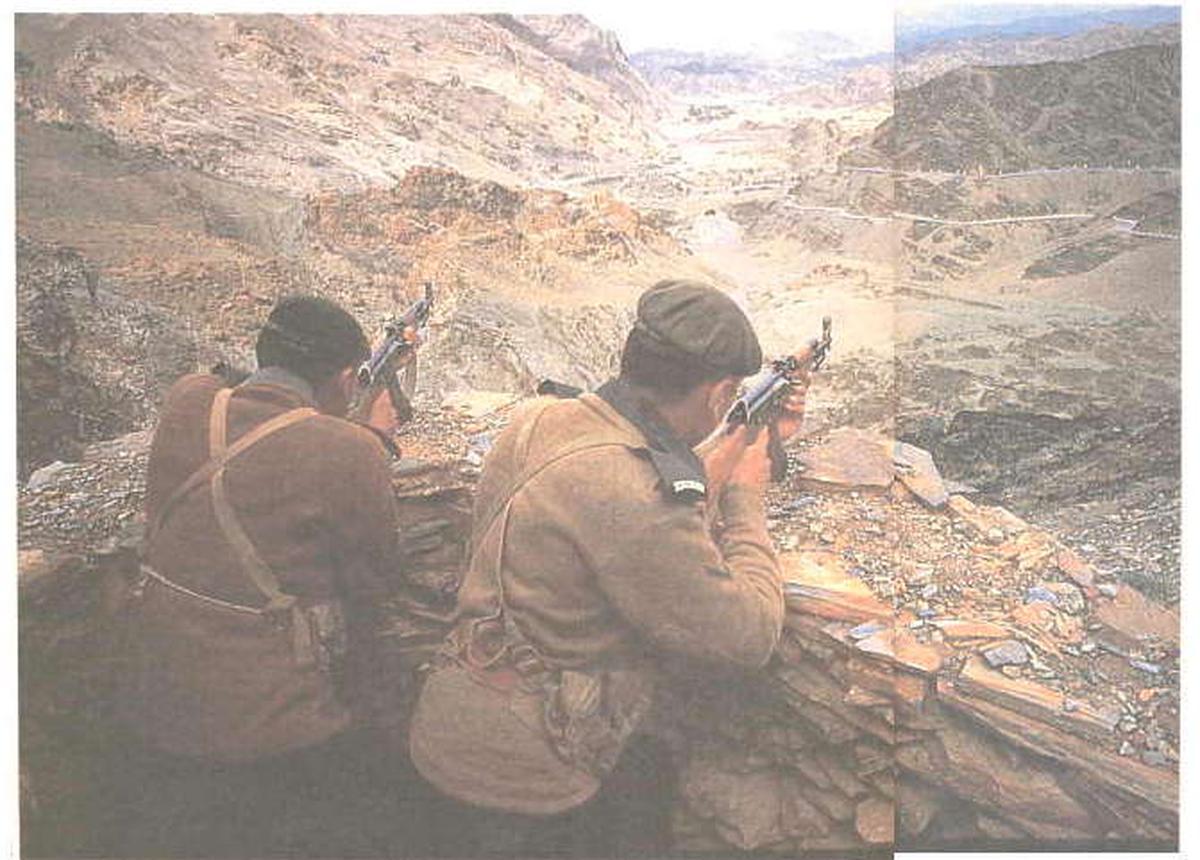

In the aftermath of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the Reagan administration saw a strategic opportunity to bleed the Soviet Union, a policy that would ultimately define the conflict. The United States funnelled billions of dollars in covert aid to the Afghan mujahideen. This assistance was not provided directly, but was instead channelled through Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). The ISI, under its then chief, General Akhtar Abdur Rahman, and later Hamid Gul, acted as the primary conduit for the U.S. arms and funds, which were then distributed to various mujahideen factions. This arrangement gave Pakistan significant control over the insurgency, a dynamic that would have long-term consequences for the region. The extensive record of this partnership, including interviews with key figures like Hamid Gul and the U.S. officials, highlights how the U.S. and Pakistan’s shared goal of expelling the Soviets laid the foundation for a complex and often contradictory alliance. This period further cemented the Republican administration’s distinctive association with Pakista. A symbolic moment of this alliance was the infamous Reagan meeting with the Afghan mujahideen leaders, who were officially referred to as freedom fighters.

The Pakistan-Afghanistan border seen in 1985.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

Then came the tenure of President George H. W. Bush , another Republican, who largely continued his predecessor’s policies in Afghanistan and toward Pakistan, even as the Soviet withdrawal in 1989 and the end of the Cold War reshaped the geopolitical landscape. His administration not only maintained security cooperation with Islamabad but also confronted new tensions, particularly over Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program, which led to the imposition of Pressler Amendment sanctions in 1990. This period also coincided with the return of Benazir Bhutto as Pakistan’s Prime Minister (PM), introducing a new political dimension to the U.S.–Pakistan relations. Her civilian leadership represented a potential counterbalance to the traditionally dominant military establishment, creating a delicate and often tenuous equilibrium between the political executive and the uniformed hierarchy. While PM Bhutto sought to assert civilian authority and pursue her own foreign policy priorities, the military continued to wield significant influence over strategic decisions, particularly regarding Afghanistan, India, and Pakistan’s relationship with the United States. This duality added layers of complexity to bilateral relations: Washington had to navigate not only Islamabad’s official policies but also the entrenched strategic perspectives of the military, whose historical experiences were shaped by partition, regional conflicts, and Cold War alliances.

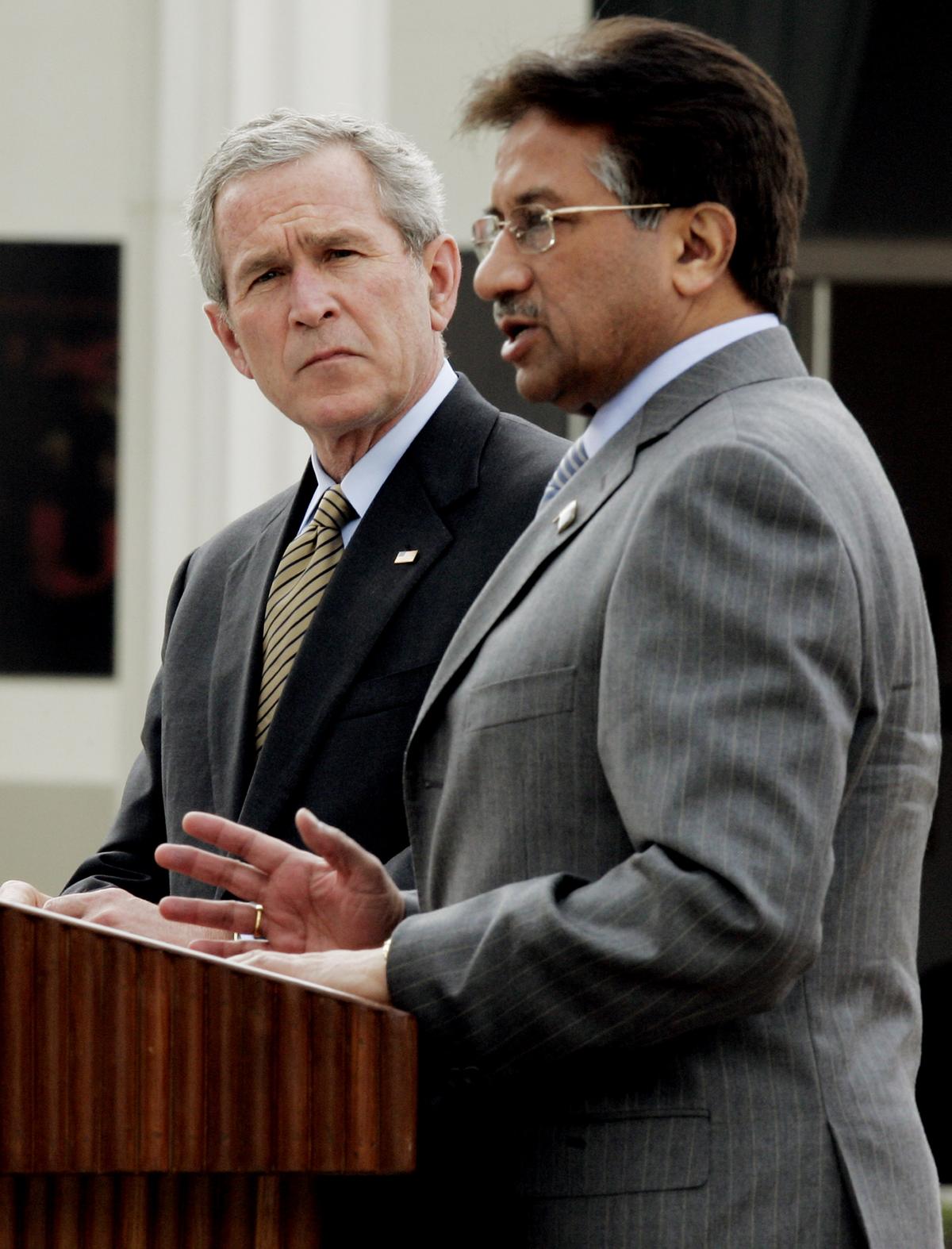

Eight-years-later, under President George W. Bush , a Republican, the U.S. policy in the region was profoundly shaped by the seismic events of 9/11 terrorist attack, which redefined both priorities and perceptions. During this time, Pakistani military once again returned to the center stage of the U.S.–Pakistan engagement.

U.S. President George W. Bush, left, and Pakistani President Gen. Pervez Musharraf participate in a joint press availability at Aiwan-e-Sadr, or “house of the President”, in Islamabad, Pakistan, on March 4, 2006.

| Photo Credit:

AP

While accidents of history do play a role, coincidences hold true only to a limited extent. The reasons are many. Since the mid-20th century, a general pattern in the U.S. foreign policy has emerged, wherein Republican administrations have tended to favor a pragmatic, security-focused alliance with Pakistan’s military establishment. This approach has often involved a de-emphasis on the promotion of civilian rule and democratic reforms. In contrast, many Democratic party-led administrations have historically been more inclined to condition U.S. assistance on human rights and the strengthening of Pakistan’s civilian government. This distinction was particularly evident during periods of shared security interests, such as the Soviet-Afghan War under President Ronald Reagan and the post-9/11 “War on Terror” under President George W. Bush, both of whom relied heavily on their military counterparts in Pakistan.

Interestingly, this strategic alignment was coupled with a certain ideological compatibility. The Reagan administration’s emphasis on Christian values and a religiously framed worldview found an unlikely resonance with Pakistan — a state created in the name of Islam. While seemingly paradoxical, this has often allowed the two nations to reinforce strategic ties through a shared opposition to Soviet communism and atheism in the past, creating a strange and powerful irony in their alliance.

This Republican party tilt towards the Pentagon is not unique to the U.S.–Pakistan relations; in other parts of the Middle East too, the contest between the Pentagon’s strategic priorities and the State Department’s more liberal, diplomacy-driven approach has often shaped policy outcomes. During the Arab Spring in January 2011, particularly at the height of the protests in Tahrir Square , there was a notable tension between the Pentagon and the U.S. State Department over the appropriate stance of the U.S. government in Egypt. While the U.S. State Department briefly prevailed, the unfolding events revealed the enduring strength of the Egyptian military, which retained both institutional cohesion and firepower. This allowed it to reassert control after the Muslim Brotherhood governance experiment failed, demonstrating the limits of popular uprisings against entrenched military structures in the region.

In sum, the current U.S.–Pakistan dynamic is best understood not as an abrupt policy shift but as the latest expression of a long-standing, security-driven relationship embedded in Washington’s institutional design. The Pentagon’s enduring rapport with Pakistan’s military, shaped by geography, strategic utility, and decades of operational cooperation, continues to operate as a constant, regardless of changes in civilian leadership on either side.

While public narratives may frame such engagements as sudden realignments or transactional bargains, they are in fact rooted in structural and historical realities: Pakistan’s placement within the U.S. strategic “Middle East” theater, the Republican Party’s historical comfort with military-to-military channels, and the mutual familiarity cultivated over generations between the Army leaderships. In this light, the renewed warmth under President Trump and General Asim Munir is less an anomaly and remind us that in the U.S.–Pakistan relations, the past is never truly past. Abbottabad itself captures this truth: what began for me as a roadside pause in 2006, became a symbol of global counterterrorism in 2011, and now endures as a reminder that Pakistan’s role in Washington’s strategic, particularly security calculus, never really disappears.

(The author has 25 years of experience as a practitioner, researcher, and analyst on conflict zones and violent extremism. His work has been published by Columbia University Press, Penguin, and Hurst.)

.